Ph.D. student has rare disease. Her own research discovered a potential breakthrough.

CHARLESTON, S.C. - When Cortney Gensemer was diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome at 19 years old, she had many questions because little was known about the rare disease.

Now, the 26-year-old may have the answers to those questions— for herself and thousands of patients— after her Ph.D. research on the topic led to a potential breakthrough. She recently obtained her doctorate from the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

"It’s kind of crazy," she told FOX Television Stations. "Sometimes it doesn’t even feel real."

Gensemer may have found the gene responsible for the group of hereditary connective tissue disorders that could possibly lead to early diagnosis and better treatment.

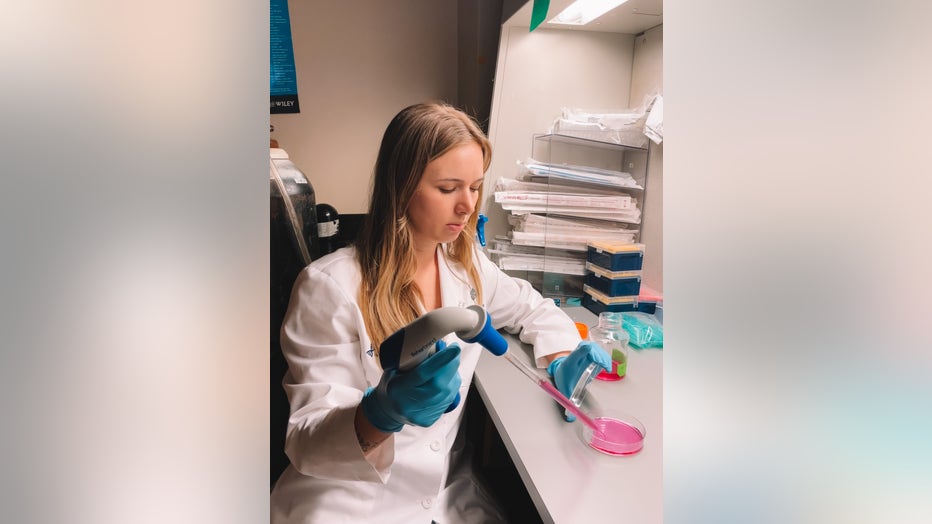

Cortney Gensemer (Credit: Cortney Gensemer)

What is Ehlers-Danlos syndrome?

According to the NIH, Ehlers-Danlos syndromes are a group of inherited connective tissue disorders caused by abnormalities in the structure, production, and/or processing of collagen— the protein responsible for healthy joints and skin elasticity, or stretchiness.

Scientists say EDS is caused by mutations in several genes, but the underlying genetic cause remains largely unknown.

There are 13 subtypes of EDS generally characterized by joint hypermobility, hyper-stretchable skin, and tissue fragility.

Symptoms vary widely and can include an increased range of joint movement, stretchy skin and fragile skin that breaks or bruises easily.

Current data suggest the prevalence of EDS is about 1 in 2,500 to 1 in 5,000 people, according to the Ehlers-Danlos Society.

Treatment can include physical therapy, pain management and surgery.

The long-term outlook for EDS patients varies based on the subtype. In the most severe cases, the prognosis can include a shortened lifespan.

Cortney Gensemer (Credit: Cortney Gensemer) ( )

Living with Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: ‘I really struggled a lot with pain’

Gensemer played sports growing up but found herself injury-prone and having chronic pain, not knowing the reason.

"I was needing to use crutches and a walker and have surgeries," she explained. "Initially, I thought I was a really tough athlete...working way too hard."

She was then diagnosed with hypermobility stemming from EDS, which causes joint pain.

Gensemer said she never heard of the disease, but then learned that many of her relatives also suffered from EDS.

"Me getting diagnosed really helped a lot of my family’s care too," she added.

Gensemer said she struggled with a lot of pain and had to find ways to manage it. She would sometimes have to lay on a heating pad in between college classes, use an icepack or take medication to numb the pain. She also had multiple major surgeries, including spinal fusion, hip surgeries and neurosurgeries.

Gensemer said she currently undergoes physical therapy to treat her pain. She also has learned her limitations, such as making sure she gets enough rest if she knows she’s going to be in a lab for an extended amount of time.

Cortney Gensemer (Credit: Cortney Gensemer)

Potential breakthrough for Ehlers-Danlos syndromes

Scientists have discovered genetic markers for most of the EDS subtypes except for hypermobility— the subtype affecting Gensemer. It’s not something scientists can detect through genetic or blood testing.

However, that could change now that Gensemer believes she has discovered the gene responsible for the subtype.

Gensemer said the discovery came after she jumped at the opportunity to study her disease four years earlier.

"Our work was really focused on trying to understand that genetic cause and find a way to diagnose patients easier," she said, adding it would also allow researchers to develop treatment.

For now, Gesnemer only describes the gene as a "strong candidate gene" for the disease but said more information and details will become available once her research is published and made public.

Though there isn’t a cure for EDS, Gensemer said knowing the gene could lead to an early diagnosis. She said that is beneficial because people can make lifestyle changes earlier in their lives, such as avoiding sports and other physical activities that come with a great risk of injury.

Gensemer said an early diagnosis could also help doctors curtail certain medical procedures, such as surgeries, to prevent further injuries on the patient.

Gensemer said that although she has her doctorate, her research will still continue as she hopes to conduct large-scale studies to understand EDS, the gene responsible for hypermobility and treatment. She has launched a registry at MUSC.

"This is definitely very much just the first start," she added. "There’s a lot to figure out, and we’re very excited to see where this goes."

This story was reported from Los Angeles.