Impact of the megadrought: Arizona cattle ranchers slashing herds to cut costs

Impact of the megadrought: Arizona cattle ranchers slashing herds to cut costs

The reality of the water crisis is stark and the effects of the southwestern region?s mega-drought continue to trickle down on cattle ranchers in Arizona. This is a look at how current drought conditions and regulations by the feds lead ranchers to sell off much of their herds.

The reality of the water crisis is stark and the effects of the southwestern region’s mega-drought continue to trickle down on cattle ranchers in Arizona.

From 2019-2021, 336,000 cattle have been sold through auctions across the state, steadily increasing year over year, according to the Arizona Cattle Growers’ Association.

This is a look at how current drought conditions and regulations by the federal government lead ranchers to sell off much of their herds.

Shrinking herds, shrinking businesses

Chino Valley in Yavapai County is just seven miles north of Prescott where the Prescott Livestock Auction is held. Inside the barn, all eyes are focused on the large herbivores front and center.

At the auction, Lisa Khan was looking to buy. She's the owner of Khan Cattle Company & Moon River Beef and has a ranch about 45 minutes away.

"We are in a town called Perkinsville which has a population of about eleven. There are three or four ranches here and that’s about it," she said. Like many ranchers across the southwest, she’s also had to make cuts to the herd.

In Arizona, ranchers lease allotments of federal land for livestock grazing. The U.S. Forest Service monitors drought conditions, evaluates climate trends, and the availability of water and forage, ultimately determining the appropriate number of livestock that can graze on the land.

In a statement to FOX 10, a U.S. Forest Service spokesperson says "it is often necessary to adjust livestock numbers following environmental stressors such as fire or extended drought in order to protect soils and vegetation and prevent ecosystem degradation."

In January 2020, Khan was told to remove her cattle from the allotment.

"Everything was too dry," she said. "There was not enough rain to grow food, so there was nothing for cattle to eat and to boot, our dirt tanks where they drink that are scattered all over the allotment – there was no water."

Khan says half of the herd had to be sold.

"Bottom line is it costs a lot of money to get kicked off your allotment," Khan said.

Now, more than two years later, she’s growing the herd back slowly.

Lisa Khan

"Total between the ranch and the farm, we have about 120 head, mother cows, and hopefully about 70 or 80 calves that either we’re going to retain as feeders and sell at the auction," Khan said.

Daniel Munch is an economist with the American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF).

He says, "Arizona is heavily owned by the federal government. A lot of farmers and ranchers are reliant on those lands, used by their cattle."

Earlier this summer, the AFBF conducted a survey on ranchers and farmers across the western, southwest, and central plains regions, receiving 652 responses from 15 states, including Arizona.

This is what they had to say about livestock production.

For the second-straight year in a row, 66% of respondents sold portions of their herd or flock due to the drought.

The survey shows out of the 67% of ranchers who cut herd size in 2021, 49% of them further reduced herd size this year.

37% planned to maintain the reduced herd size while 14% want to rebuild the herd in the near future.

Click here for an interactive map.

Business practices evolving

Munch says the ongoing drought can devastate a rancher’s livelihood.

"We already have reports of ranchers closing down their operations either temporarily or indefinitely because they can no longer support the animals on their land," Munch said.

His report found that 90% of respondents saw increases in local feed costs linked to the drought.

Khan can attest to rising prices.

"The price of hay is going up, so it’s tremendously expensive to feed your cows, especially $100 a head, it’s really quite costly," Khan said.

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, parts of Arizona are in "severe drought." Some are in "moderate drought" and other portions are "abnormally dry" after two active monsoon seasons.

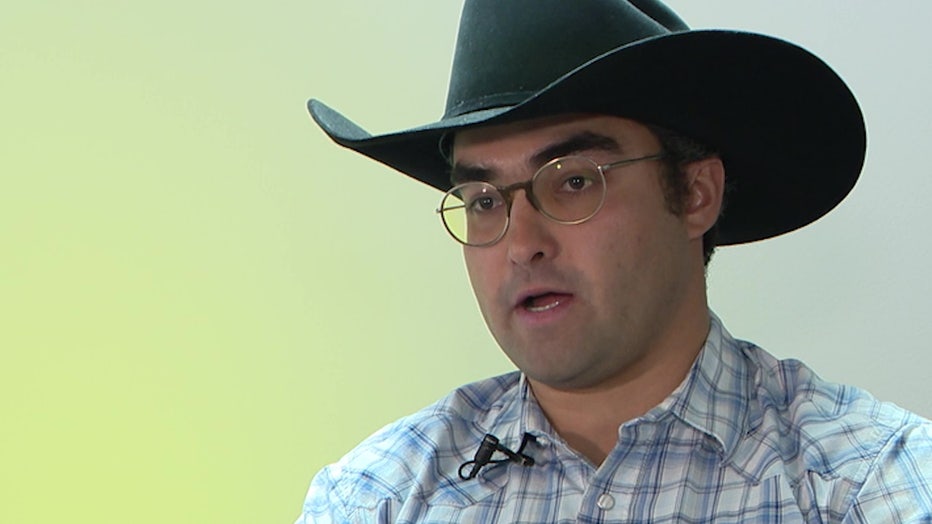

Alexander Khan

Khan's son, Alexander Khan, knew they had to innovate.

"During the pandemic, we kind of wanted to rethink how we went about things," he said.

He started a website under Moon River Beef, marketing how their cattle are raised, allowing customers to order online and have meat delivered straight to their homes at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The main challenges, he says, are navigating the drought and having to move cattle off federal land.

"We’ve been leasing land, and we have irrigated pastures where we’ve been putting our other cattle, so we can continue to have a viable business," he said.

In October, the Arizona Cattle Growers’ Association wrote a letter to the Prescott National Forest supervisor, asking if decisions to stock allotments with cattle are "based on facts and science", transparent, and fair to permittees."

"We’re trying to create a better working relationship with the Forest Service so that they can experience our needs, and we can try to move to the middle and meet theirs as well," his mom, Lisa, said.

Alexander adds, "They could cut you off your allotment, and you’re done. I mean, your business is dead. You can’t earn a living anymore. That’s a serious consequence – the economics behind it, the human stories behind it of people just losing everything."

‘We have to conserve our resources …'

"What does it mean for consumers? For consumers, it means over the next two, three years prices are gonna increase once we cut through all the excess supply from heavily liquidated cattle counts," Munch says.

Alexander believes ranching is a generational business.

Sustainability over the next several decades will always be at top of mind as climate change and the drought threaten this way of life.

"I think there’s this misconception that ranchers are anti-environment, or they don’t care about the drought, or they’re just grazing their herds and destroying all the grass and moving on and that’s not the case. Most ranches are quite small, and so we have to conserve our resources in order to survive," Alexander said.

What's next?

In the meantime, the Center for Biological Diversity and the Maricopa Audubon Society warn that a lawsuit will be filed against the Forest Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife. Advocates for endangered species in aquatic areas of the Tonto National Forest call for officials to restrict cattle grazing which they say is destructive.

Related reports:

- In Arizona, worry about access to Colorado River water rises

- 'We’re driving toward a cliff': Crisis looms without big cuts to Colorado River

- Winners, losers in Colorado River water cuts for Western states

- Drought-stricken Arizona to get less Colorado River water

- Arizona lawmakers rewrite Ducey’s plan for $1 billion for new water

Arizona's megadrought: The latest and what can we do to help

The federal government is expected to restrict Arizona's water supply even more in the coming months, heading into the new year. We're taking a look at problems that may be coming down the pike and what various Arizona water districts are doing about it, and what you can do too.

City of Phoenix holds town hall meetings amid ongoing megadrought

The megadrought has forced Phoenix, along with other Valley cities, to adopt measures aimed at reducing water usage, as water allotment cuts come into force. FOX 10's Justin Lum reports.

Drought-stricken Arizona to get less Colorado River water

For the second year in a row, Arizona and Nevada will face cuts in the amount of water they can draw from the Colorado River as the West endures an extreme drought, federal officials announced on Aug. 16. FOX 10's Nicole Garcia reports.

'It feels like there is a big target on agriculture's back': Arizona farmers says the drought's impact is dire

Some farmers in our state have seen reduced water for their crops, while other farmers have already run dry. Like most mornings, Nancy Caywood loads up in her car and drives around her 250-acre farm, Caywood Farms. The dust kicks up behind the back wheels and in a few days, she says her farm will be even drier.

Drought-stricken Arizona to get less Colorado River water for the second year in a row

Lake Mead is currently less than a quarter full and the seven states overall that depend on its water missed a federal deadline to announce proposals on plans cut additional water next year.