Deepfake: What is it, and why is it so dangerous?

PHOENIX - The topic of deepfake has been at the front of public discussion lately following two incidents that involved well-known American figures.

On Jan, 22, the Associated Press reported that the New Hampshire Attorney General's Office is investigating reports of an apparent robocall that used artificial intelligence to mimic President Joe Biden's voice. The message reportedly discouraged the state's voters from voting in the primary election that was set to happen on Jan. 23.

Just days later, the AP reported that sexually explicit deepfake images of singer Taylor Swift were circulating widely on the social media platform X (formerly Twitter), with the images eventually winding up on Facebook and other social media platforms. It was later reported that X had blocked some searches for Swift in response to the situation.

Here's what to know about deepfake, and why some are very concerned about it.

What's deepfake?

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines deepfake as "an image or recording that has been convincingly altered and manipulated to misrepresent someone as doing or saying something that was not actually done or said."

Meanwhile, the Oxford English Dictionary offers a similar definition for deepfake. There, it is defined as "any of various media, especially a video, that has been digitally manipulated to replace one person's likeness convincingly with that of another, often used maliciously to show someone doing something that he or she did not do."

When was the term coined?

An article published on the MIT Sloan School of Management's website states that the term was first coined in late 2017 by a Reddit user of the same name who created a space on the site where people "shared pornographic videos that used open source face-swapping technology."

How are deepfakes made?

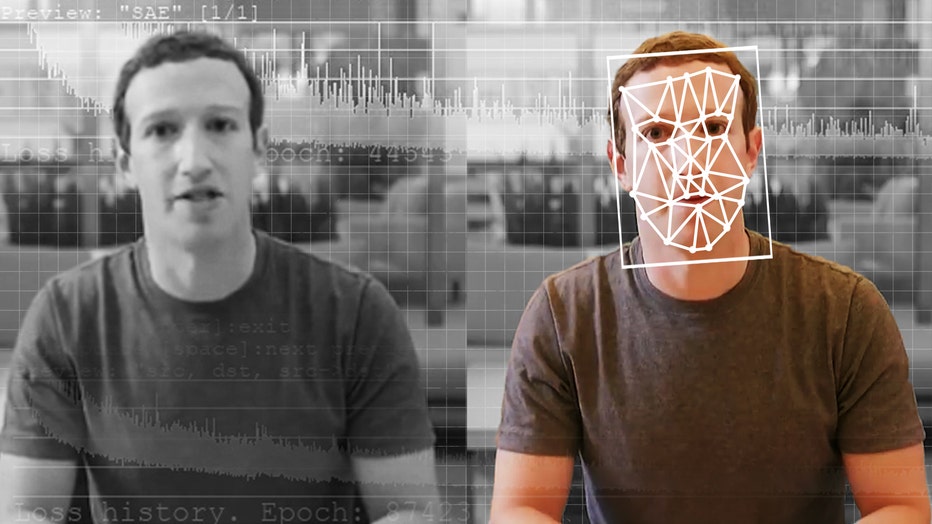

A comparison of an original and deepfake video of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. (Elyse Samuels/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

The article on MIT's website detailed the steps that are needed to create a deepfake video.

"To make a deepfake video, a creator swaps one person’s face and replaces it with another, using a facial recognition algorithm and a deep learning computer network called a variational auto-encoder [VAE]," a portion of the article read, citing a research assistant at the MIT Media Lab. "VAEs are trained to encode images into low-dimensional representations and then decode those representations back into images."

According to the article, a VAE would be trained on images of the face of the person you want to make a deepfake of, while another VAE would be trained on "images of a wide diversity of faces," with further facial recognition algorithms applied to video frames, in order to "capture different poses and lighting conditions that naturally occur."

Afterwards, it was stated that the two encoders would be combined, which results in the deepfake target's face on someone else's body.

What are some examples of deepfakes?

The two aforementioned incidents involving Taylor Swift and President Biden are examples of deepfakes. Another example involving celebrities include a TikTok account that posts video of a person who bears the likeness of actor Tom Cruise.

The article on MIT's website also provided an example of deepfake: a video featuring the late Former President Richard Nixon announcing a failed moon landing. That video combined actual footage of Nixon's resignation speech with the text of a speech that was prepared in case the first Apollo moon landing failed.

The failed moon landing speech was indeed drafted, according to records on the National Archives website, but it was never used because the Apollo 11 astronauts landed on the moon and returned to earth safely, rendering it moot.

(NOTE: The YouTube video above is a deepfake video showing an AI-generated person with the likeness of Former President Richard Nixon making a speech that was made in preparation for a possible failed Apollo 11 moon landing. The speech, as featured in the video, was never made by Former President Nixon, and is used to illustrate what a deepfake video can look like.)

Yet another example was cited in a report on deepfake published by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security: in 2020, there were reports of "new music" being released by famous artists, living and dead. As it turns out, programmers created realistic tracks of new songs by Elvis, Frank Sinatra, and Jay-Z.

In the case of Jay-Z, the report states that the artist's company sued YouTube to take the tracks down.

A less harmful example of deepfakes, according to the University of Virginia's Information Security Office, involves the use of face-swapping apps.

"You’re probably familiar with the amusing effects of "face-swapping" on Snapchat or other photo apps, where you can put someone else’s face on your own and vice versa. Or maybe you participated in the "age yourself" trend, and ran your face through a fake aging app that showed you what you might look like in your ripe old age," a portion of the website states. "Aside from the fact that these applications of photo-altering technology are designed for amusement, they’re mostly harmless because it’s easy to tell that the images are fake and don’t actually reflect reality."

What are the criticisms of deepfake?

Impact on politics

An article published in 2023 by UVA states that political experts at the university are raising the alarm that "political operatives could develop attack ads using computer-generated ‘deepfake’ videos and recordings and deploy them at the last minute to turn the tide of an election."

"The potential to sway the outcome of an election is real, particularly if the attacker is able to time the distribution such that there will be enough window for the fake to circulate but not enough window for the victim to debunk it effectively (assuming it can be debunked at all)," wrote UVA cyber privacy expert Danielle Citron, in the article.

A 2018 incident cited in a 2020 article on deepfakes by the magazine IEEE Spectrum highlights the problem deepfakes can pose in politics. The example involves the governor of a Brazilian state who was engaged in a sexual act. The governor insisted it was a deepfake.

Impact outside of politics

(KIRILL KUDRYAVTSEV/AFP via Getty Images)

Some say deepfakes can have an impact beyond politics. For example, an article published on the website for UVA's Information Security Office states that in some situations, deepfakes can be used in acts of fraud.

"On a small scale, deepfakers can, for example, create personalized videos that appear to show a relative asking for a large sum of money to help them out of an emergency and send them to unsuspecting victims, thereby scamming innocents at an unprecedented level," the article reads.

In 2019, cybersecurity firm Trend Micro published an article that illustrated the potential deepfake can have on fraud: a United Kingdom-based energy company lost US$243,000 as a result of a deepfake audio where the voice of the parent company's CEO was cloned by AI in order to facilitate an illegal fund transfer.

Perception of truth

MIT Technology Review published an article in 2019 on how the mere idea of AI-synthesized media is making people stop believing that real things are real.

"Deepfakes do pose a risk to politics in terms of fake media appearing to be real, but right now the more tangible threat is how the idea of deepfakes can be invoked to make the real appear fake," the author of a report on deepfake said, in the article.

The article also cited a 2018 example in Gabon, a country in Africa where its leader at the time was the subject of speculation over ill health. The country's government released a video on New Year's Eve that year that shows the leader delivering a New Year's address, which led to speculation the video was deepfake.

"Subsequent forensic analysis never found anything altered or manipulated in the video. That didn’t matter. The mere idea of deepfakes had been enough to accelerate the unraveling of an already precarious situation," a portion of the article read.

Is the term being misused?

In an article published by the magazine IEEE Spectrum, it is stated that computer vision and graphics researchers are "united in their hatred of the word," as the word has become a catch-all term "to describe everything from state-of-the-art videos generated by AI to any image that seems potentially fraudulent."

"A lot of what's being called a deepfake simply isn't: For example, a controversial ‘crickets’ video of the U.S. Democratic primary debate released by the campaign of former presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg was made with standard video editing skills. Deepfakes played no role," read a portion of the article, which was published in 2020.

Is there a potential for deepfakes to be used positively?

In 2019, TechCrunch published an article on the matter, which states that deepfakes have "the potential to plug the technological holes in smart assistants and digital influencers."

"[Deepfake] could grant smart assistants the capacity to understand and originate conversation with much more sophistication. Similarly, digital influencers could develop the ability to visually react in a believable way in real time, thanks to deepfake tech," read a portion of the article. "Bringing Mickey Mouse to life beyond a Disney cartoon or guy in a suit at Disneyland is where we’re headed. 3D hologram projections of animated characters (and real people) that are able to speak in a realistic sounding voice, moving like their real world counterpart would."

Deepfake technology has also been used in advertising. In 2023, an ad by the Brazilian arm of German carmaker Volkswagen featured a popular singer from that country, Maria Rita, with her mother Elis Regina, a popular singer in her own right who died in the 1980s.

The ad, according to the website Creative Bloq, features a person with the likeness of Regina driving an old model VW vehicle, as Rita was driving a newer model. The ad was made to mark the company's 70th anniversary in Brazil.

Creative Bloq's article on the ad did state that the video was at the center of a certain level of controversy, mostly because Regina, having died decades ago, couldn't give consent for her likeness to be used in such a manner. Officials with Volkswagen said the ad was approved by the singer's family.

Another, less controversial example of using late celebrities in videos involves the movie Furious 7. The article published on IEEE Spectrum claims that Paul Walker, who died while filming the movie, was featured in parts of the film via deepfake technology.

Are deepfakes legal?

On the website norton.com, which offers a variety of cybersecurity-related software, it is stated that there are currently no federal laws that govern deepfakes.

However, it is stated that as of September 2023, there are six states – Georgia, Hawaii, Minnesota, Virginia, Washington and Wyoming – that have laws regulating deepfakes. Meanwhile, two other states – California and New York – allow people to sue deepfake creators in civil court.

How can I spot deepfakes?

Norton.com listed several ways people can spot deepfakes at this time, including:

- Unnatural eye movement

- Unnatural facial expressions

- Awkward facial feature positioning

- Lack of emotion

- Awkward-looking body or posture

- Unnatural body movement

- Unnatural coloring

- Blurring or misalignment

- Video is not being reported on by trustworthy news sources

The site also states that reverse image searches can "unearth similar videos online to help determine if an image, audio, or video has been altered in any way."

Are there Deepfake detectors?

Various deepfake detectors have been developed, including one that was developed by Intel.

However, per a July 2023 article published by the BBC states that Intel's deepfake detector managed to classify several real, authentic videos as deepfakes. The article's author reached out to a research scientist at Intel on the false positives, who said the system was being overly cautious.